Five years after Rabaa: From generation protest to generation violence

On 14 August 2013, Egyptian security forces raided two large sit-ins that were occupied for six weeks by those protesting the military coup that removed Mohammed Morsi, Egypt’s first democratically elected president. The raids were described by Human Rights Watch as "one of the world’s largest killings of demonstrators in a single day in recent history".

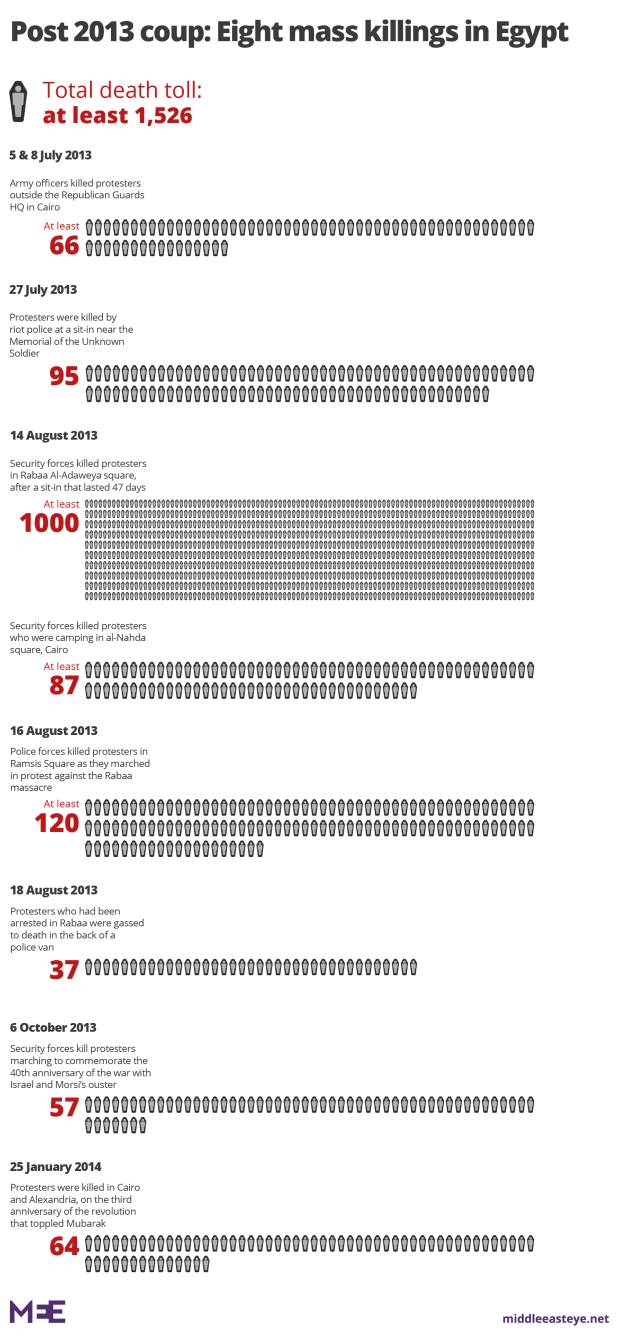

Over 1000 protesters were killed on one day.

A break with the Arab Spring

The Rabaa massacre represented a break with the post-Arab Spring trajectory that began with the promise of a democractic opening and ended with repression as the new status quo.

For nearly three weeks, from 25 January until the former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak ended his three-decade reign by transferring power to the Supreme Council of the Armed forces (SCAF) on 12 February, the world watched in awe as the Egyptian people transformed their dream of freedom into a reality.

And yet that was a dream short-lived. Repression quickly returned under the military rule of the former Minister of Defense-turned president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. Sisi has created a breeding ground for youth to turn to violence, as they could no longer see a place for themselves in the institutions of governance nor trust the democratic process that was violently aborted in Rabaa.

The Rabaa massacre represents a break with the post-Arab Spring trajectory that began with promise and today finds it establishing repression as the new status quo

Five years after the Rabaa massacre, the socio-political situation is worse. Today, Egypt detains over 60,000 political prisoners and has built 16 more prisons to handle the overflow. The youth that Amnesty International once referred to as "Generation Protest", is now "Generation Jail". According to the Egyptian Coordination for Rights and Freedoms, in 2016 there were 830 cases of torture.

Police forces continue to torture detainees systematically with impunity. A 2015 Amnesty report on domestic, public and state violence against women in Egypt was called, "Circles of hell". Over 1,250 people have disappeared in recent years about whom there is no information. At least 240 political activists and protesters were arrested between April and September of last year on charges either relating to online posts, which authorities deemed "insulting" to the president, or for participating in unauthorised protests.

Mass unfair trials targeting peaceful protesters, journalists and human rights workers, as well as sweeping death sentences and the closure of NGOs and civil society organisations –including the shut down of El-Nadeem Center, an NGO that provided support to survivors of torture and violence - further choke civil society.The government has also intensified its crackdown on press freedoms. Over two-dozen journalists remain in prison. The state has blocked 434 news and information websites (including Mada Masr and Daily News Egypt) and continues to block -and regularly filters- Egyptian users' content.

In March 2017, the minister of justice referred two judges to a disciplinary hearing for participating in a workshop organised by an Egyptian human rights group to draft a law against torture. In just three months last autumn, authorities sent at least 15,500 civilians to military courts, including over 150 children.

Furthermore, the president has renewed and extended the 1958 Emergency Law that gives unchecked powers to security forces to arrest and detain and allows the government to impose media censorship and order forced evictions.

A weaker economic state

Today, over fifty percent of Egyptians live on less than $1.80 per day. Egypt has over 20 million citizens aged between 18 and 29, and with over 25% of them unemployed, uncertainty about the future becomes daunting. In the 1970s and early 1980s, an Egyptian entering the labour market with a secondary education or higher had a seventy percent chance of securing a public sector job, today those in the same pool have a fifteen percent chance.

The flotation of the Egyptian pound in late 2016 nearly halved its exchange value from $0.112 to 0.057, leading food prices to skyrocket as inflation reached almost 35 percent. Among the lessons learned from military coups that occurred in Latin America, Africa and Asia, is that military regimes consistently fail to foster economic development, rendering them incapable of devising and implementing successful economic models.

When a military, like that of Egypt, is both entrenched in the deep state and in the economy, it operates in the best interest of the military and not of the people. Economic schemes like the expansion of the Suez Canal did not deliver on their promises, and left Egyptians in a weaker economic state. And while the regime was celebrating the expansion, nine political prisoners died in state custody.

Phases of violence

With no avenue for Egypt's disenfranchised youth to voice their political discontent -and the state choosing repression over engagment- places like Egypt may become recruiting grounds for violence. Violence and terror occur in a progression.

With last winter’s terror attacks on mosques and religious leaders who seemed to support the regime, a phase two had been entered - attacks on those who support the regime had begun. The question is what will be done to prevent the start of phase three.

An Uncertain Future

The beauty of the 25 January revolution was the seemingly spontaneous, pluralistic and peaceful nature it took. However, after years of increasing repression in Egypt, as the level of frustration escalates, military repression with violence may lead to the militarisation of the youth.

And with the reinstating of military aid to Egypt last week by the United States, it seems that the democratic preconditions are no longer a barrier to military aid, and thus no longer of interest to the international community.

The question remains of the lessons learned. What the Rabaa massacre showed the world is that thousands can be killed and a revolution ended with no political or economic consequence to the regime. But what is the cost to the people?

There will be another push for change at some point. There will be a counter-revolution, and the impunity witnessed in Rabaa signals that it just might not be peaceful.

-Dalia Fahmy is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Long Island University and Senior Fellow at the Center for Global Policy.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.

Photo: Demonstrators with Egyptian Americans for Democracy and Human Rights hold a rally to mark the anniversary of the Rabaa Massacre in Cairo in August, 2014 (AFP).

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

New MEE newsletter: Jerusalem Dispatch

Sign up to get the latest insights and analysis on Israel-Palestine, alongside Turkey Unpacked and other MEE newsletters

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.